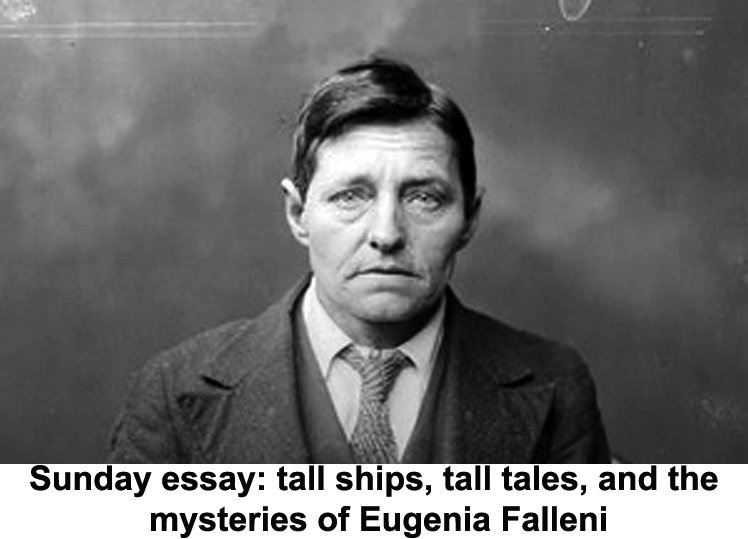

Eugenia Falleni in 1920. An Italian-born-woman-turned-Sydney-dwelling-man,

Falleni was convicted of murder in 1920.

I’m an unlikely sailor of tall ships. Too clumsy, too prone to motion sickness, too white and nervous about symbols of colonisation. Nevertheless, in 2013 I found myself up the mast in the middle of the Tasman sea, surrounded by nothing but open ocean.

I was researching a novel about Eugenia Falleni, an Italian-born-woman-turned-Sydney-dwelling-man who was tried for the murder of his wife in 1920. As the commonly told version of the story would have it, Falleni “disguised herself” as a cabin boy and sailed from Wellington to Sydney on a Norwegian barque in the last years of the 19th century. According to some enthusiastic (but factually dubious) accounts, Falleni “roistered” around the Pacific, calling in at Honolulu, Papeetee, and Suva, drank with men, and passed as a man, but arrived in Sydney pregnant.

This “Norwegian barque” was a Schrodinger’s box, and Falleni was the cat. Falleni was man and woman in the same instant, and only tunnelling back through time, lifting a hatch on the deckhouse roof and peering in would decide the moment when Falleni, in the eyes of those watching at least, switched from one gender to the other. Many of Falleni’s biographers have tried to imagine the moment of the onlookers’ “discovery”. As a would-be novelist, I had to as well.

But where to start? Too under-confident in my concept to approach anyone from the transgender community, I started with the ship. If I could get the realist details of the external world right, I told myself, perhaps the interior, psychological uncertainties would resolve themselves in the process. Procrastination disguised as research, perhaps, but I did not know that then.

A Google image search of barques revealed that one was – bizarrely for the 21st century – sailing from Sydney to Auckland, almost exactly the reverse passage Falleni would have made in 1897. I lost a few hours clicking through links that led to sites, which led to my booking a berth as voyage crew on the STS Lord Nelson, set to leave Darling Harbour for Auckland on October 10 2013.

The Lord Nelson is not Norwegian, but wannabe time travellers can’t be too fussy. “Nellie”, as she’s affectionately known by those who sail her, is owned and worked by the South Hampton-based Jubilee Sailing Trust, an organisation established in the late 1970s to make off-shore sailing a possibility for those with special needs.

Despite Nellie’s mod-cons, my first night beyond the heads was a waking nightmare. The voyage crew slept below decks towards the bow of the ship in an area called the fo’c’sle. The fo’c’sle is far from the stabilising main mast, moves the most, and is the worst place to be if you are feeling queasy. It thrashed up and down, side to side, while we tried to sleep on shelves masquerading as bunks, our green faces nudging and retreating from the lee cloths that kept us in our beds.

We could hear the slurp and spray of the Tasman as it slammed against the porthole windows. Something aggressive barged at the hull repeatedly, and the aftershocks made the ship quiver like a dog in a thunderstorm. In my sleepless paranoid state I was convinced hammerhead sharks were head-butting the keel, trying to get at the tender voyage crew inside. (Later I would learn that the noise was made by the anchor rolling around in the anchor locker.)

Over the following nights, most of us gingerly made our way from our bunks to the stairs in the lower mess, then waited for the ship’s roll to help our weakened legs climb the stairs onto the deck. Once on deck we had to clip onto the safety wire that ran around the deckhouse and vomit into paper bags before flinging them into waves, which loomed five metres above us on the windward side of the ship, or dropped, suddenly, from beneath.

The ship would nuzzle into these waves, before rising on their peaks, tilting, then sliding down into a temporary gully. Why did I think this state of interminable queasiness would help me with a novel? I was literally, and figuratively, at sea.

All at sea

It was a feeling of motion-sickness that originally inspired me to write about Eugenia Falleni. In 2005, Sydney’s Justice and Police museum hosted City of Shadows, an exhibition of long-forgotten police photographs recovered from a flooded warehouse. I left the exhibition with the accompanying book, and later pored over the photographs for traces of the suburbs I thought I knew. One picture in particular captured my attention: a mugshot of a man in a cheap suit and tie, his short hair combed into a sideways part.

What struck me most was the melancholy in the subject’s eye; how brow-beaten he looked. To me, he seemed composed, but so close to the verge of a nervous breakdown that I was physically jolted out of being a passive viewer. I flipped to the back of the book to read a brief footnote:

Eugenie Falleni [sic], 1920, Central cells. When hotel cleaner “Harry Leon Crawford” was arrested and charged with the murder of his wife three years earlier, he was revealed to be in fact Eugenie Falleni – a woman and mother who had been passing as a male since 1899…

Turning back to the portrait of the sad man, his face — or my perception of his face — morphed into that of a woman’s. But in the moment that he, the sad man, morphed into she, the “cross-dressing murderer”, I have to admit that the thrill I felt was associated with my own jolt in perception; like the moment Escher’s black birds turn into white birds flying in the opposite direction. What would it be like to live your life oscillating between what others expected to see?

I had, up until this voyage at sea, written hundreds of thousands of words that did not ring true. Possibly this bad writing was due to a nervousness that what I was attempting was culturally insensitive. I am not transgender, I am not working class, I am not, and have never been, Italian. Should I even be attempting to write Falleni’s story? In the interests of forging the most respectful way forward (and appeasing my guilt), I did eventually meet with a trans man my supervisor knew. I was anxious going into the meeting, because I wasn’t entirely sure what I was asking from him. Did I want his permission? And if he gave it, what then?

My fears, it turned out, were founded. While he generously gave me his morning, he seemed a little frustrated by the need to have to explain that his experience as a trans man was going to be very different to another trans experience, especially one lived a hundred years ago. I flushed with embarrassment. Of course I didn’t want him to suddenly be the spokesman of the entire trans community, no, not at all.

Sitting across the table from him, my cold coffee growing skin as I babbled, I realised how condescending the categories of identity politics can be. While they are vital in giving the disenfranchised a collective voice, identity politics can also flatten the myriad possible expressions of how people might live between genders into one “type” — where one person’s experience can stand in for another’s.

Deviants to dysmorphia

Falleni told detectives that they dressed as a man for the economic opportunities. According to the local Sydney tabloid press, Truth, Falleni told detectives they “thought it better to give up life as a woman, because they worked for long hours for a small wage”. But Falleni also married two women and owned a dildo (also held in the Justice and Police Museum’s collection) — and presumably engaged in sexual relationships with women. Living at a time that did not have a language for what would now be considered transgender experience, it’s not surprising Falleni avoided citing sexual or instinctual reasons for passing as a man.

At the time of Falleni’s trial, the term used to describe anyone not living a hetero-normative existence was a “sexual invert”, a pathological condition of deviancy. Falleni’s barrister, Archibald McDonnell, vaguely suggested that Falleni was such an “invert” by arguing that Falleni had “the masculine angle of the arms”. The judge interrupted McDonell’s cross-examination of the government medical officer to ask if he was making an insanity plea, proving that, at the time, there was confusion about whether “sexual inversion” was a sexuality, a physiological type, or a diagnosis of mental illness.

But as historian Ruth Ford argues, it was not in the interest of the Crown to classify Falleni as an invert, because it would have “detracted from their case, which emphasised Falleni’s deceptive nature — her fraud and lies”.

Since Falleni’s arrest, various attempts have been made to categorise Falleni’s gender-crossing. In 1939, Dr Herbert M. Moran wrote that Falleni was a “homosexualist” and suggested their “disorder” was congenital. He wrote:

She was condemned even from her birth and her abnormality derived from the very nature of her being. The temperamental outbursts, the vulgar debauches, the filthy speech, were but minor manifestations of her interior disorder.

In his 2012 biography of Falleni, Mark Tedeschi diagnosed “gender dysmorphia”, reporting that

her female bodily attributes were like having an unwanted, additional limb attached to her body that she overwhelmingly felt did not belong to her.

Others have resisted classifying Falleni’s gender and sexuality. Alyson Campbell, director of Lachlan Philpott’s 2012 play about Falleni, The Trouble with Harry, admits to having initially wished to impose a lesbian subjectivity on Falleni’s story. However she conceded that neither lesbian or trans identities were “available to a person such as Falleni, navigating a way through the undocumented, secret world of being a female husband.”

I did not want to invade Falleni’s very private existential conundrum and claim their identities for my empire (read: my cv), and yet I couldn’t shake the story off.

What kept drawing me back was not an urge to answer the questions of who Falleni was (which are not my questions to answer), but rather an urge to come to terms with how Sydney dealt with the uncertainties that Falleni’s various identities posed. The shock remains fresh: Falleni’s trial occurred almost 100 years ago, and although the terminology we use to discuss cases like this has changed, the tendency to categorise and scrutinise “abnormal” behaviour hasn’t.

This was also a story about patriarchy, how its control is insidious and polices everyone — men and women and those who are neither or both — at every level of bureaucracy. Though my experience is by no means comparable to Falleni’s, this is something I have experienced first-hand.

A stranger amongst men

When the seas died down around Nellie, we were well clear of land. Surrounded by nothing but open ocean, my life now depended on something as small as a house, as buoyant as a bath toy, something only as strong as its shipwrights knew how to make it.

Sexual innuendo was social currency on the ship, and your first voyage was a test, to see if you could take it. It was fun, at first, to be around authority figures who couldn’t give a shit about “minding their manners” and affecting professional decorum. It helped that the first mate Leslie — a woman — had stripes, and was just as crass as the men.

I ended up staying on from Auckland to Wellington, this time as a trainee bosun’s mate, the volunteer crew responsible for maintaining the ship’s equipment. On this leg a watch leader presented me with a lock that had fallen off the ladies’ toilet door in the fo’c’sle, along with four very short screws. I found Leslie and the Captain in the chart room and asked Leslie what she thought I should do with it.

She looked at me incredulously. “Fix it.”

“Right,” I said, “but where are the screws?”

“You’ll have to get them from Mr Chips,” she said.

“Ah, but Pip,” the Captain said, “I’d be careful how you ask Chips for a screw.”

I found the second engineer, Mr Chips, on the stern platform with the first engineer, Marco, sitting in a coil of rope and sipping his third cup of tea for the day.

“Chips,” — I was already on the defensive — “I know how this is going to go, but I need four long screws.”

Chips said nothing for a while.

“Right,” he eventually said, “well you’ll find them in the container in the middle of the workshop.”

Marco groaned at the wasted opportunity.

Negotiating sexual innuendo with the cook was more precarious. When a handful of us were asked to scour the hot galley, I volunteered to scour the lard that had accumulated under and behind the ovens. At one point I had my torso wedged under the ovens, and my arse had nowhere else to be but high in the air. Derek the cook stood behind, supervising. The next day he sat beside me while I was sitting on the deck.

“I think you visited me last night in my dreams,” he said softly. “But you weren’t wearing French knickers when you cleaned the ovens, were you?” The comment was meant to be funny, but it made me weary. Really? I thought. Is this how it’s going to be? The game was: they prodded, and you deflected. It was both exhausting and boring.

Later, in the bar, I told Derek he was a sleaze. I said it publicly, and jovially, knowing “preciousness” would not be tolerated. Mr Chips inhaled sharply and Derek’s face fell. An unspoken rule of the ship became clear to me: women should take a joke, but an accusation of sexual impropriety — even if made in good humour — would not be tolerated.

Derek’s revenge came at dinner. My meal was loaded with so much chilli powder, I could barely swallow it. He didn’t talk to me for three days, but by the time we reached Napier he was cracking jokes about my “free passage” with a playful elbow in the ribs. I laughed along, to show him I could take it.

After we’d tied up in Wellington, Marco and I were taking a moment to recover from the wind over a cup of tea in the upper mess.

“So, what are you writing about?” he asked.

I told him the spiel. By then, I’d learned it by rote.

“Falleni…” Marco said, trying out the name, “so she was Italian? Of course she was. I bet she was hairy, too,” he chuckled, and shot a knowing look at Mr Chips.

As he did, I thought I saw a horse passing by on the dock outside. I did a double take. Yes, there was a horse out on the dock, being led by a woman in a shabby suit and bowler hat. She turned to look at the ship, and I saw her moustache, the whiskers growing out of her cheeks.

“Oh my God,” I said, and pointed out the window behind his back. He turned to look, and there were more women now, all in shabby suits and moustaches.

Marco turned back, unfazed. “So the wife, she had to know.”

“Well, apparently not,” I said, on automatic pilot, transfixed by the scene out the window.

“But how did they fuck?”

“With a dildo,” I said. “It’s on exhibit at…”

The women began to chant. They were on strike. They were re-creating the Great Strike of 1913 for the museum over the road, but it was the world of my novel and it was real and it was right outside the window.

During the month I spent in Wellington, I wrote the first part of my novel that stuck. It had nothing to do with sailing ships, nothing to do with being a spokesperson for a transgender experience that was not mine to share, and everything to do with being a fish out of water: a stranger amongst men.

Postscript

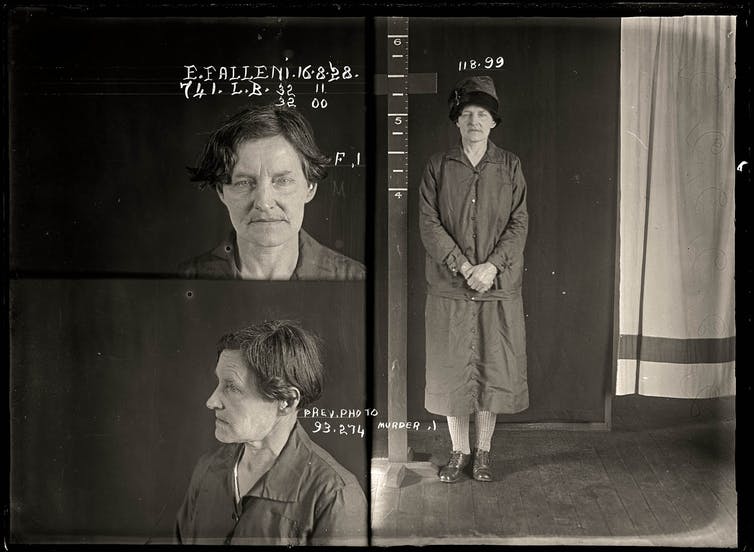

Eugenia Falleni was sentenced to death for the murder of Annie Birkett on October 6 1920, but shortly afterwards this sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. Falleni was released from Long Bay Penitentiary in February 1931, after which they lived as Jean Ford, and built a successful business as a manager of “residentials”.

On June 9, 1938, Jean Ford sold her Glenmore Road “residential” business for £105, and on the same day was hit by a car on Oxford St. Ford was taken to Sydney Hospital, but died on June 10, aged 63. Throughout their lives, Falleni maintained their innocence.

A year after my voyage on Nellie, Suzanne Falkiner re-released her 1988 biography of Falleni with revisions and new information. There were details that hadn’t jumped out at me before. The main one suddenly rendering redundant months and thousands of dollars worth of research: Falleni probably didn’t travel to Sydney by a “Norwegian barque” at all. The son of one of Falleni’s New Zealand friends recalled that

the last time [Falleni] met my mother, [Falleni] told her that she was going to work her way as a stoker [someone who stoked a fire for a ship’s engine] on a ship to Australia, which she did. After she arrived in Australia, she [or someone who wrote for her] wrote to my mother saying she had arrived safe and that she hardly slept at all on board ship and kept an iron bar under her pillow for protection.

A stoker? On board a barque? Not likely. In becoming obsessed with the mysteries of Falleni’s identity, I had ignored details that were not convenient to my own myths. Or perhaps I wanted to go to sea, be at sea, a little while longer.

This essay was written by:

NB: in this article, I have chosen to refer to Falleni according to their surname, for its gender-neutrality, and have used the pronoun “they” when referring to Falleni’s collective self, and “he” or “she” for Falleni’s particular identities that presented as decidedly male or female.

Pip Smith’s novel, Half Wild, has just been published.

This article is part of a syndicated news program via