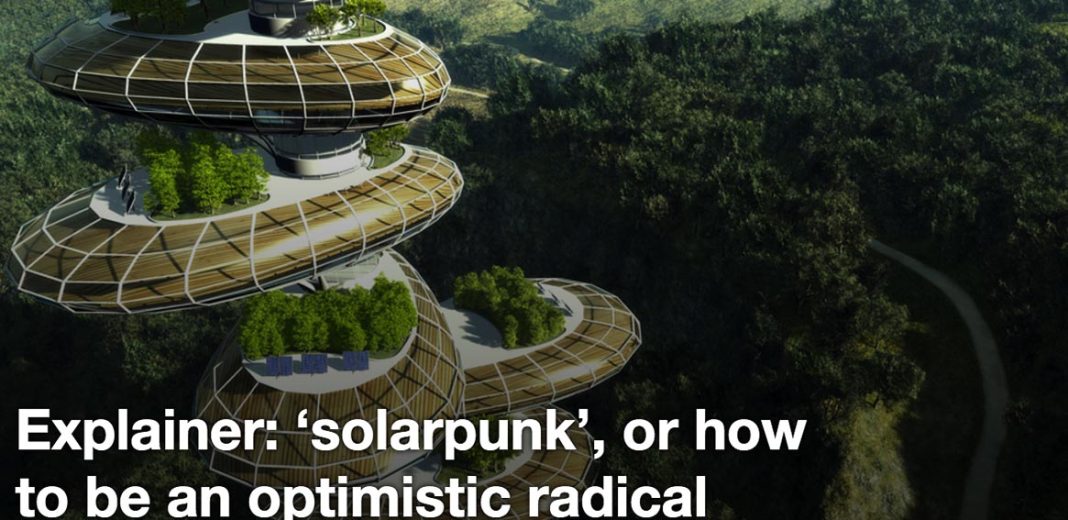

Solarpunk imagines a

sustainable future, and what it might be like to live in it.

Solarpunk imagines a

sustainable future, and what it might be like to live in it.Punks (of the 70s and 80s kind) were not known for their optimism. Quite the opposite in fact. Raging against the establishment in various ways, there was “no future” because, according to the Sex Pistols, punks are “the poison / In your human machine / We’re the future / Your future”. To be punk, was, by definition, to resist the future.

In contrast, the most basic definition of solarpunk — offered by musician and photographer Jay Springett — is that it is a movement in speculative fiction, art, fashion and activism

that seeks to answer and embody the question ‘what does a sustainable civilization look like, and how can we get there?’

At first pass, then, Solarpunk seems to turn the central tenet of punk on its head. Its business is imagining the future. Moreover, perform an online “image search” for the term “solarpunk” and you will find colourful, leafy metropolises, flowing neo-peasant fashions and, perhaps, a small child standing next to a solar panel in front of a yurt.

How, then, are the bright futures imagined by solarpunks, worthy of the “punk” suffix?

Solarpunk’s optimism towards the future is the first concept that needs complicating here. Along with the original punks, there is a wide body of scholarship that critiques positive thinking. Feminists like Barbara Ehrenreich and Sara Ahmed, for instance, trace links between the capitalist establishment and happiness. They suggest that future-centred optimism serves the very system raged against by most punks of old.

An animated version of Barbara Ehrenreich’s criticisms of positivity.

Although optimistic, Solarpunk’s future imaginings do not fit neatly with current political regimes or economic systems. Self-described “researcher-at-large” Adam Flynn argues that the movement begins with “infrastructure as a form of resistance”. Solarpunks are in the business of dreaming a totally different system of energy delivery, essential services and transport. Quite different to behemoth of roads and coal-fired power plants we live amongst today.

In other words, Solarpunks resist the present by imagining a future that requires radical societal change. Radical, perhaps, but not radically impossible. Indeed, many of the technologies and practices that solarpunks draw into their imaginings already exist: solar and other renewable energy, urban agriculture, or organic architecture and design. Like sci-fi authors, solarpunks remix the present to produce an alternative future.

Apocalypse or utopia?

In a fictional sense, solarpunk sits across the table from “cli-fi”. In recent years, the term cli-fi has moved from a fringe concept to a marketable genre of fiction. Coined in the first instance by Dan Bloom, it has grown so big that scholarly researchers are able to produce studies of the conventions. New novels and short story collections are now published in this category each year.

Cli-fi, in both film and fiction, tends towards dystopia. For film, watch The Day After Tomorrow, in which New York is flooded and frozen in climate mayhem, and Snowpiercer, where efforts to control climate change go dramatically awry. For text, look for Paolo Baciagalupi’s The Water Knife, in which drought has devastated the south western US. These are stories of failure, disaster, and social collapse. Crucially they represent the apocalypse as catalyzed in some way by climatic or environmental change: wave, snowstorm, drought. Cli-fi has really just replaced earlier anxieties (such as nuclear war) with new ones (such as out-of-control geoengineering).

In the Australian context, Briohny Doyle’s The Island Will Sink and James Bradley’s Cladetake up these themes. Here too, cli-fi can be seen in novels written before the concept existed, in what Ken Gelder calls “rural apocalypse fiction” such as Carrie Tiffany’s explorations of failed semi-arid land farming in Everyman’s Rules for Scientific Living.

I teach “cli-fi” in a literary studies course, including Doyle’s and Tiffany’s novels, and I invite students to critique the apocalyptic nature of the genre. Is it a problem that the future is only imagined as spectacular disaster or slow decline?

Solarpunks argue that the problem with imagining such a dark future (or no future, for that matter) is that, while failure may be cathartic it thwarts the possibility of thinking about alternatives.

As a genre of writing, solarpunk has its predecessors. The Fifth Sacred Thing (1994) by Starhawk and Ernest Callenbach’s Ecotopia: The Notebooks and Reports of William Weston (1975) both imagine anti-capitalist, de-urbanised, garden-centric societies. Although Callenbach’s text is not a perfect utopia (as if there is such a thing), he is on record as stating the need for alternative future visions in a similar manner to solarpunks. In film, the work of Hayao Miyazaki provides a mainstream forerunner to the aesthetics and political challenges of the movement.

The trailer of Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke

Discovering the rainbow

As a category of fiction, solarpunk remains a fringe dweller. Its few self-identifying authors describe their additions to the genre as a positive reaction to grim science fiction. Examples in this vein are Biketopia: Feminist Bicycle Science Fiction Stories in Extreme Futures and Sunvault: Stories of Solarpunk and Ecospeculation. Solarpunk fiction is either self-published or supported by small independent presses, with mixed reviews.

On Instagram #solarpunk yields under 1,000 uses. Nevertheless, the aesthetic sensibilities of the subculture are starting to emerge. A few fashion enthusiasts post selfies experimenting with flowing fabrics, cool coloured lipstick and body piercings. If steampunk is when “goths discover brown”, solarpunk is when they discover the rainbow.

On Twitter, the hashtag is more common. It groups together self-published tales, fashion statements and even instances wherein the solarpunk project might be seen to break through into the present day, as in the case of electric buses. It also seems that, like its predecessors steam and cyberpunk, solarpunks do dabble in costumes (cosplay).

It’s also political. Andrew Dana Hudson says that the subculture “posits a world of solar-energy abundance and then argues that we will still have need of punks. No magical tech fixes for us. We’ll have to do it the hard way: with politics.” To be solarpunk, then, is to mount a resistance to the mainstream present by imagining an alternative future.

The question that remains for me in all this is what differentiates a solarpunk from an ecosexual, or an ecofeminist technopagan, or an eco-afrofuturist or even a permaculturist? Or, indeed, other colourfully clad, politically oriented utopian movements?

Similarities abound, but the focus on the cultural change that will necessarily accompany the full transition to renewable energy is the defining feature of solarpunk.

This is what I find deeply compelling about the subculture. We usually ask “can renewables replace fossil fuels?”. It is an important question, but it does not grapple with the links between culture and energy. Thus instead solarpunks ask “what kind of world will emerge when we finally transition to renewables?” and their writings, designs, blogs, tumblrs, music and hashtags are generating an intriguing answer.

This article was written by:

This article is part of a syndicated news program via