Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

The Morrison government will this week announced its long-awaited electric vehicle strategy, coinciding with COP26 climate change talks underway in Glasgow. The new policy contains some welcome new funding, but is largely notable for what it omits.

In a welcome move, the government has allocated an additional A$250 million for electric vehicles, primarily aimed at charging infrastructure. But unlike every leading electric vehicle market globally, the plan delivers no financial or tax support to help Australian motorists make the switch to a cleaner car.

And the government has failed to explain how the policy will help Australia achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, just as it failed to do when releasing its economy-wide emissions reduction plan last month.

It’s encouraging to see the Morrison government move past its claim of a few years ago that electric vehicles would “end the weekend”. But the new plan is not the national electric vehicle strategy Australia deserves, and badly needs.

Falling short

Transport produces almost 20% of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions – 60% of which is from cars. And the rate of transport emissions is fast increasing.

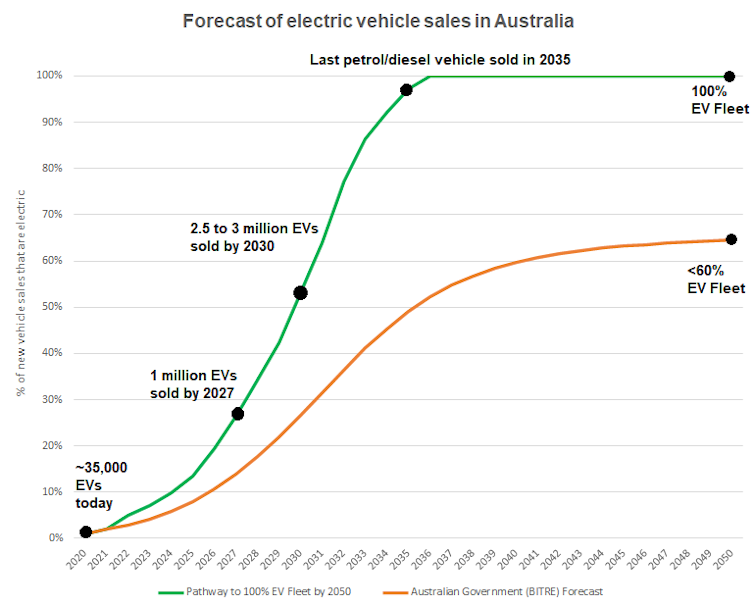

The government says the policy, titled the Future Fuels and Vehicles Strategy, will lead to 30% of all new car sales being electric by 2030 – which would mean 1.7 million electric cars on Australian roads.

But in 2019, government modelling predicted electric vehicles would comprise 27% of new sales by 2030. So the new measures announced will lead only to a 3% increase in what would have happened anyway.

At COP26 last week, Australia signed a global agreement to make electric vehicles the “new normal” by 2030. One in three cars being electric vehicles hardly meets this goal.

Most concerningly, the government’s plan is inconsistent with global targets to achieve net zero emissions by 2050. The United States, for example, is aiming for at least 50% electric vehicle sales by 2030.

Oddly, it appears the government would prefer Australian motorists remain dependent on expensive, foreign fuel for transport. Its investment in July of $260 million to increase diesel reserves – notably more than the new electric vehicle funding – supports this theory.

Read more: Scott Morrison spruiks electric vehicles – but rules out subsidies and an end-date for petrol cars

Australia’s token effort

Globally, about 5% of all new cars sold are electric and this is rapidly increasing. Yet in Australia, the figure is about 1%.

So what measures does the new strategy contain to shift the needle? In two words, not much. It includes:

- $250 million to support public charging infrastructure, fleet infrastructure, vehicle trials and smart charging infrastructure in households

- continued low-interest financing support for fleets via the Clean Energy Finance Corporation

- an overdue update to the Green Vehicle Guide.

It’s better than nothing. But the government has claimed electric vehicles will deliver around 15% of national emission reductions required by 2050. It’s hard to see how the measures released today will get us there.

The government has also claimed high international demand for electric vehicles could constrain global supply and slow deployment in Australia.

But as carmakers have pointed out, they have little reason to send new, cheaper electric models to Australia because it lacks the policies to stimulate electric vehicle demand.

The plan Australia deserves

The Morrison government must go back to the drawing board and produce a national electric vehicle strategy consistent with global climate efforts.

That would mean aiming for at least half of new car sales being electric by 2030, and 100% by 2035. This translates to about one million electric vehicles sold in Australia by 2027 and at least 2.5 million by 2030.

It’s a massive increase from the 30,000 or so electric vehicles sold over the past five years, and at least 50% higher than what’s forecast under today’s strategy.

Australia can learn much from overseas jurisdictions on how to boost electric vehicle sales. Until electric vehicle targets are met, the following state and federal policies are needed:

- increase supply by introducing a national sales mandate for electric vehicles, and penalise manufacturers that don’t meet them

- reduce upfront costs by making electric vehicles exempt from GST, stamp duty and registration fees (as is done in Norway)

- support fleet adoption by making electric vehicles exempt from fringe benefits tax

- fund infrastructure by committing to support the rollout of 100,000 public charging points by 2027 (in line with the European Union’s target).

- Penalise states that go it alone on taxing electric vehicle usage. Instead, focus on road charges that address Australia’s multi-billion dollar city congestion problem rather than unfairly taxing rural and regional electric vehicle drivers due to the longer distances they have to drive.

Read more: Going electric and banning new petrol-powered cars could be Australia’s next big light bulb moment

Why Australia must act

The benefits of electric vehicles go far beyond tackling climate change.

We estimate Australians spend more than $30 billion each year on imported fuel. This alone should be enough to spur governments to support electric vehicle adoption and keep this money in Australia.

Recent analysis by the Australian Conservation Foundation also found maintaining the current approach to transport emissions could cost Australia up to $865 billion between 2022 and 2050.

Aside from greenhouse gas emissions, the costs were attributed to air, noise and water pollution. But better zero-emission transport policies could enable Australia to reduce these costs by up to $492 billion.

Clearly, electric vehicles deliver a net economic benefit, even after accounting for the cost of incentives and loss of fuel tax revenue.

As the rest of the world charges ahead, the Morrison government’s new strategy looks ever more foolish.

This article is the result of a collaboration between:

Disclosure statement

Dr Jake Whitehead is the Tritium e-Mobility Fellow at the Dow Centre for Sustainable Engineering Innovation at The University of Queensland, holds an Advance Queensland Industry Research Fellowship focussed on how electric vehicles can deliver co-benefits to the energy sector, is a Member of the International Electric Vehicle Policy Council, is a Lead Author of the AR6 Transport Chapter for The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and Director of Transmobility Consulting. He has previously received government funding for several sustainable transport projects, including research on both hydrogen and electric vehicles. His UQ position is not funded by Tritium, and he does not recieve any income from the company. His position is named in recognition of the advanced manufacturing company being founded by former engineering graduates at The University of Queensland.

Kai Li Lim is the inaugural St Baker E-Mobility Research Fellow at The University of Queensland’s Dow Centre for Sustainable Engineering Innovation. His position is endowed through the St Baker Energy Innovation Fund, but he does not receive any income from any of its portfolio companies.

Jessica Whitehead does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.